Tri: release notes

Tri is an experimental image distorter. You can choose an image to render using a WebGL quad, adjust the texture and position coordinates to create different distortions, and save the result.

Understanding WebGL textures

Tri is a direct result of my attempts to understand how texture mapping works in WebGL. I’ve used WebGL (by way of Three.js) in several projects, but I’ve never felt confident in my understanding of how it worked. Part of it is that I’ve always been interested in using it for 2D stuff, where the vast majority of the info is (understandably) for 3D applications.

Recently, however, I found the WebGL Fundamentals site and started reading through their tutorials. Several of the early tutorials go through WebGL in terms of replicating methods from the HTML Canvas API. I’ve gotten used to canvas through the Constraint Systems experiments, so this was a great way for me to come at it.

(Sidenote: all the time I’ve been working with canvas, I’ve had a nagging feeling that maybe I should be using WebGL instead, since it’s generally so much better performance-wise. I was happy to find that a lot of that knowledge actually transfers over, and working with canvas has been good preparation for WebGL.)

Going through the WebGL Fundamentals examples on textures, I learned that you can do a lot of 2D work with WebGL by building out a sprite sheet and applying textures from it using the equivalent of canvas’s drawImage() method. This is roughly how many of the grid-based Constraint Systems’ projects work, meaning (I think) that I could convert them over to WebGL without too much trouble.

Triangles

Before I started any conversions I wanted to explore a bit more about how WebGL works differently from canvas, though. Specifically, I wanted to try and get more of an understanding of the implications of everything being made of triangles. To replicate canvas’s drawImage() which takes source and destination rectangles, you put together two triangles to make a quad. How a texture is applied in WebGL is based on two arrays. positions sets the position of the verticess that make up the shape (in this case two triangles). textures sets the coordinates for where the texture is sampled from. Both are fed into WebGL as flat arrays, 12 coordinates long (2 triangles * 3 vertices per triangle * 2 coordinates (x and y) per vertex).

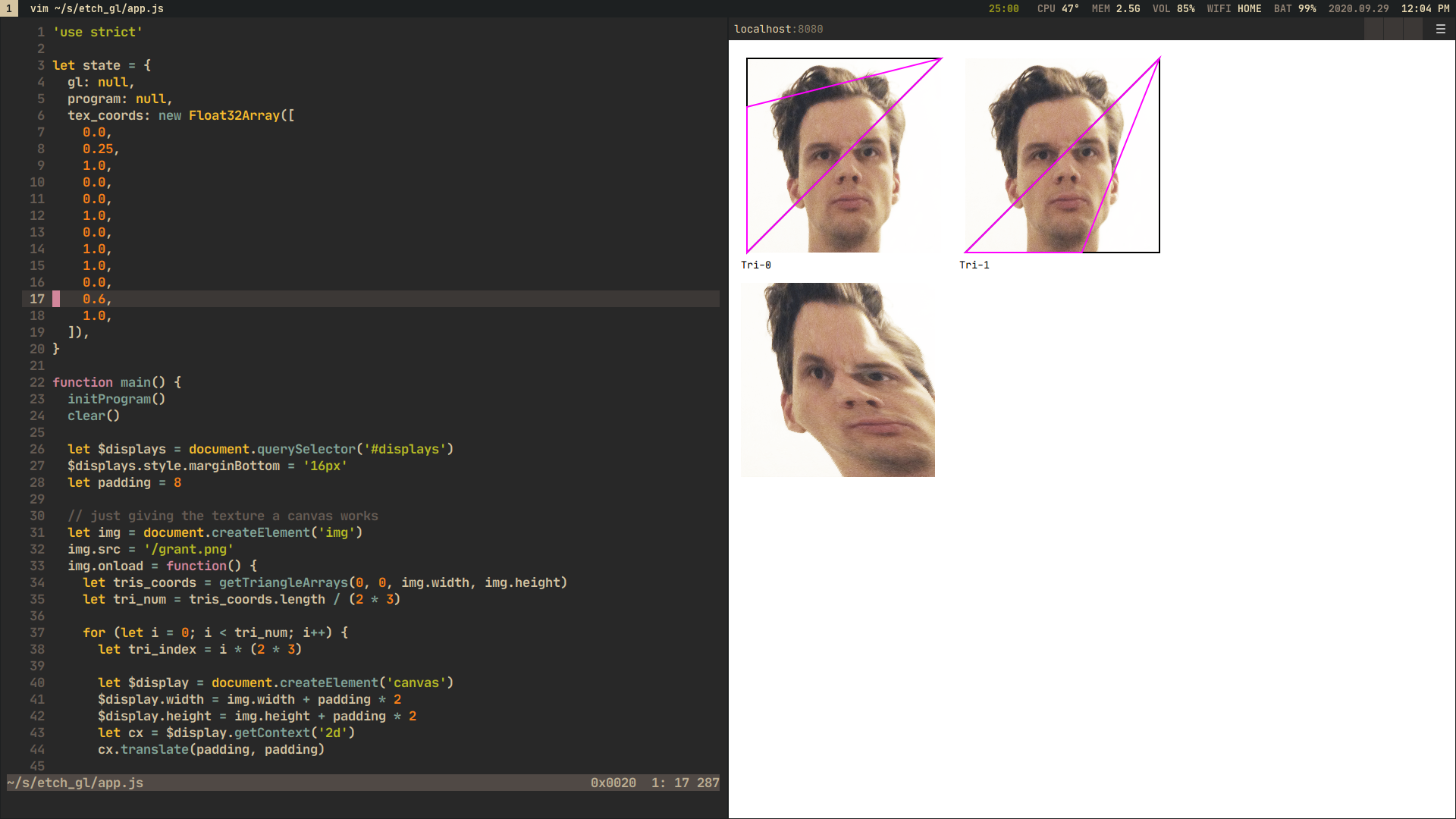

An early version of the texture experiment.

To understand those triangles I started visualizing the arrays, drawing them (using canvas) over the top of a source image, displayed next to the WebGL render. There was a little bit of work to translate between clipSpace's 0-1 and the pixel values of canvas. WebGL Fundamentals gave a good rundown of ways to do this. I think before I’d found clip space off-putting. Now, having implemented my own zoom functions several times, I get the logic of keeping space relative until the final rasterization step. It was a bit fiddly to figure out in which order to draw the triangles based on the flat array, but I got there eventually.

After getting the canvas visualization and the WebGL render to work in tandem, I started to explore what kind of distortions you could get from changing the texture coordinates. It’s an interesting set of behaviors, a result of both the triangle primitives and how it stretches/interpolates pixels (this is determined in part by the texture clipping settings, which based on WebGL Fundamentals I set to CLAMP_TO_EDGE and NEAREST). It can get pretty funhouse mirror-like. I also like how you can mirror the texture by folding the texture coordinates over on themselves.

The set of behaviors was interesting enough that I built out the rest of Tri, making the coordinates adjustable by clicking and dragging. I ended up locking the coordinates for where the triangles meet together. Making an object called quad_map that contained the coordinates for switching between thinking of the quad as four points and the actual six coordinates it is in the WebGL internals. Using that object as glue, Tri translates the adjustments you make pretty directly into the WebGL buffers themselves.

Forward

Having completed Tri, I think I’ll look more at transferring some of the existing Constraint Systems projects into WebGL. At least until I get sidetracked by another interesting interaction bit that I decided to make an experiment out of.